Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Article written by Jean Pierre Fava and kindly and patiently reviewed by Mgr. Dr. Edgar Vella, curator of the Museum of the Mdina Metropolitan Cathedral.

At the crossroads between Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, Malta has been not only a cradle of Mediterranean civilizations, but one of the decisive scenarios where European identity has been forged, over and over again, throughout the centuries. From the Greeks to the Romans, through the Normans and the Moors, many have sought to rule the Maltese archipelago but were eventually defeated by proud locals. Today, its many Christian heritage sites reflect the islands multicultural past and present, offering visitors a true glimpse of the universality of the Christian message in general, and of Malta’s rich history and deeply rooted faith in particular.

In fact, Marian devotion on the island of Malta goes back to early Christianity. Some would suggest it might even go back to Paul’s famous shipwreck in the island, as told in the biblical book of the Acts of the Apostles.

It is a well-known fact that the New Testament says very little, almost nothing, about how Jesus looked like. It doesn’t say anything about the looks of the apostles either. The same goes for Mary: there is not a single Christian scripture from apostolic times providing any details about her appearance either. It is no surprise then that artists relied, from the very dawn of Christianity, on the many different artistic canons of their day and age and not on the written testimony of their own Christian communities when they had to portray either their Messiah or any other character considered important, may it be in icons or frescoes.

Tradition holds that one of those early artists was also the physician responsible for authoring one of the Gospels, and for being Paul’s scribe and companion throughout his apostolic journeys: Luke himself. Eastern churches consider him as the original “iconographer,” responsible for “writing” the first icon of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In fact, Luke was traveling with Paul when they shipwrecked off the northwestern coast of Malta, spending the unnavigable winter months there. Luke’s presence in the Maltese archipelago might explain why both historical artifacts and oral traditions provide evidence of a very early Marian devotion spread throughout these islands.

Even more, Luke is not only traditionally credited with the authorship of the very first Marian image of Christianity: his Gospel is by far the most Marian of them all, brimming with the seeds of what would later grow into full Mariological theological developments. Maltese traditions claim that it is likely that Luke spoke to the islanders about the Mother of the Savior. Here, we want to present you with a collection of some of the legendary Marian icons of Malta.

1.- The Hodegetria at the Mellieha National Marian Shrine

According to a tradition, this moving image of the Blessed Mother dressed in a purple cloth and holding Christ child on her lap was painted directly on the rock by the Evangelist Luke in AD 60, when he reached Malta with Saint Paul. Recent assessment by art historians show that the present version of the icon dates to the 13th century. The style of the mural reveals classic features of Byzantine iconography. The Blessed Virgin Mary is depicted as a majestic figure, wearing the color of royalty (purple) and looking at the viewer with proud eyes. A flower on her forehead stands as a symbol of her virginity while her finger points at Christ Child as the source of salvation. This pictorial arrangement, known as Virgin Hodegetria (“The Virgin who shows the way”), was typical of Byzantine Marian icons during the 11th and 12th centuries. Since its creation, the icon has attracted pilgrims from all over the world, including Pope John Paull II, who famously prayed in front of the icon in 1990. Together with twenty other Marian shrines, the Mellieha National Shrine is currently part of the European Marian Network. It is very probable that Christian practice, on this site and the cave-church embracing this icon, vastly predates the present 13th century Siculo-Byzantine icon. Indeed, a tradition confirms this and relates that in AD 409, a number of Catholic Bishops visited the hallowed grotto and consecrated it as a Church. This happened very close to the Council of Ephesus of AD 431 when the Blessed Virgin was universally recognized and acclaimed as Theotokos, (Birth-giver of Christ God – Mater Dei in Latin). Therefore, it is possible that the present icon of the Mater Dei is not the first icon of the Virgin in this sacred place.

*The Icon of Our Lady of Mellieha: A Journey through the multi-disciplinary conservation project, Valentina Lupo and Maria Grazia Zenzani (Aletier del Restauro Ltd.). Treasures of Malta No. 67 Christmas 2016, Volume 23, Issue 1.

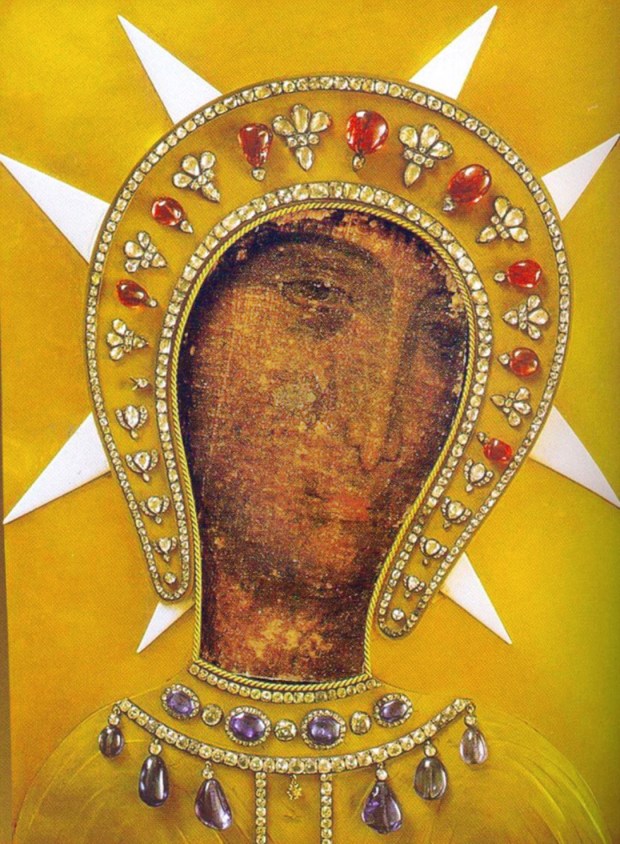

2.- St. Luke’s Madonna at the Mdina Metropolitan Cathedral

This icon depicting the Virgin with the Child Jesus held at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Saint Paul, in the old Maltese capital of Mdina, owes its name to the long-held belief that Saint Luke authored it, in the first century. However, art historians now agree that it probably dates to a later moment of Christian history, probably the Middle Age period. Its presence at the Cathedral can be traced to at least 1588. This icon played a crucial role for local believers. The Madonna and Child was also carried annually during the procession held at Mdina in thanksgiving for the Great Siege victory. In 1604, local Bishop Gargallo decided to place it on the main altar of the Cathedral. He also covered it with a silver lamina leaving visible only the faces of the Blessed Virgin Mary and her child Jesus. Gargallo’s order had been duly executed, since by 1615 this icon stood on the main altar beneath the great polyptych of St Paul. In 1618, Bishop Cagliares thought it wise to have the Blessed Sacrament placed on the Privileged Altar dedicated then to Our Lady ‘del Soccorso,’ and the St. Luke Madonna appeared on this altar, for the first time, in the records of the 1634 Pastoral Visit. The earliest reference to a Cathedral in Mdina dates back to 1299.* However, the present Baroque cathedral was built between the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th centuries, after the old one was severely damaged by an earthquake which hit Sicily and Malta in 1693. Once the new cathedral church was built, this precious icon retained the same predominant allocation assigned to it by Bishop Cagliares. It was placed on the altar of the Blessed Sacrament chapel where it has remained ever since. In 1898, Pope Leo XIII authorised the official coronation of the “Saint Luke Madonna.”

*Letters by Pope Gregory the Great to Lucillus, Bishop of Malta, dating between AD 592 and AD 599, show that Malta already had a fully-fledged Christian community with its own Church and Bishop. Tradition holds that after St Paul’s shipwreck and stay in Malta (AD 60), Publius, the Roman Governor, became Malta’s first Bishop.

3.- Marian Icons of The Greek Catholic Church

The 12th century icon of “Our Lady of Damascus” (Damaskinì – in Malta known as the Damaxxen) and the 14th century icon of “Our Lady of Mercy” (Eleimonitria) were brought to Malta by Christian refugees that escaped from the Greek island of Rhodes following Islamic invasions. Here, the two icons found a safe refuge in the Greek Byzantine Catholic Church of Our Lady of Damascus. Both icons display a color scheme typical of Syrian icons, gold and dark purple, and depict the Blessed Virgin Mary looking straight into the viewer’s eyes as she holds Christ Child in her left arm. However, the Eleimonitria seems always to have been in Rhodes in its own church. On the other hand, the more ancient icon was originally venerated in Damascus (Syria), whence it took its name. It was said to have reached Rhodes under miraculous circumstances in 1475. From the first the Damaskinì was intimately associated with the other wonder-working icon, the Eleimonitria. For instance, when the Turks besieged Rhodes in 1522, the two icons were taken, for safety’s sake, to the church of St. Demetrius within the city walls. The Knights of St. John held the two icons of the Mother of God in great veneration, as did the local Maltese population. Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette, in particular, was a fervent devotee and prayed regularly before the Damascene icon, especially during the Great Siege of 1565; and when the siege was raised, the grateful Grand Master prayed before the icon of Our Lady in the Greek church (at the time in Birgu; and also named Vittoriosa after the Great Siege victory) and there presented his hat and sword as a votive offering and gesture of gratitude. They still hang there, even though the Greek church is in Valletta, since 1832.

*Borg V., Various Marian Devotions – The Damascena. Marian Devotion in the Islands of St. Paul. 1983. The Historical Society 1983

*Buhagiar M., The Virgin of Damascus in the Greek Catholic Church, Valletta, Malta The Shared Veneration of a Miracle-Working Icon. Department of Art and History, University of Malta

4.- The icons of the Blessed Virgin of Philermos (Black Madonna of Malta) and the Caraffa Madonna at St. John’s Co-Cathedral

The Magnificent St. John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta houses the Chapel of the Madonna of Philermos (aka Panagia Filevremou, Blessed Virgin of Philerme and Black Madonna of Malta), built to house the icon of the Madonna of Philermos. This Chapel is also the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament. The icon was brought over to Malta by the Hospitallers (The Order of St. John), today known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (S.M.O.M), after being defeated in Rhodes and expelled. According to tradition, the icon had been brought to Rhodes by a pilgrim returning from the Holy Land. The Order of St. John considered two sacred images as its most holy relics – the Hand of St John, a gift by the Turkish Sultan to the Grand Master at the fall of Jerusalem, and the Madonna of Philermos. The Knights considered this icon to be miraculous. The Madonna of Philermos was venerated by the Order since they settled in Rhodes in 1307. When Malta was surrendered to Napoleon in 1798, Panagia Filevremou was stripped of its precious ornaments and followed Grandmaster Hompesch into exile. Today the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament holds another glorious icon: the silver-clad icon of the Caraffa Madonna, which is carried in procession every year on the day of the Immaculate Conception, the 8th of December. The Caraffa Madonna was donated to the Conventual Church by the Prior Fra Girolamo Caraffa. Its original collocation was the tondo on top of Mattia Preti’s altarpiece of the Coronation of Saint Catherine in the Chapel of the Italian Langue. It was only after the Madonna of Philermos was taken away in 1798 that the Caraffa Madonna was relocated to the Chapel of the Madonna of Philermos.

After leaving Malta, the icon was given to Czar Paul I of Russia, who had been elected Grandmaster of the Order. During the Russian revolution of 1917 the icon was taken out of Russia, and given to the Czarina Maria Feodorovna who kept it till her death. After other vicissitudes it was entrusted by the Russian Orthodox clergy to King Alexander of Yugoslavia, who kept it in Belgrade. At the time of the German invasion in 1941 it was removed from the capital and taken to Montenegro. After that all traces seem to have been lost. Recently, it was traced in Montenegro, kept in the National Museum. It seems that as the Germans were advancing, the icon was entrusted to a monastery. During Tito's rule the police managed to lay hands on it, and took it to Belgrade. Eventually the government decided to return it to Montenegro, and today is still kept at the National Museum.

*Restoration Of St John’s Co-Cathedral now focusing on ‘Black Madonna’ chapel. The Malta Independent, 23 August 2009. Accessed January 2021.

* Zammit Cabaretta A. The Order of St. John and the Devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Marian Devotion in the Islands of St. Paul. 1983. The Historical Society 1983. Accessed January 2021

5.- Our Lady of Victories icon at Our Lady of Victories Chapel

In the Church of Our Lady of Victory in Malta’s capital, Valletta, one can find a Byzantine Icon of unknown origin. Tradition maintains that it was given to the Church by Grand Master Adolf de Wignacourt (1601-1622 AD). The icon has a delicately painted copper face and finely engraved silver riza. This church was erected in 1567 as a thanksgiving to Virgin Mary for her help in fighting off Islamic invaders during the Great Siege of 1565. The church was built on the site where a religious ceremony was held to inaugurate the laying of the foundation stone of the new city Valletta on 28th March, 1566. For its first ten years, the church served as the first place of worship of the legendary Knights of the Order of Saint John. On the 21st August 1568, Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette (1495-1568 AD), who financed from his own pocket the construction of this church, died after suffering a severe sunstroke while hunting at St Paul’s Bay. Originally, he was buried in his beloved Church, but later his remains were buried in the crypt of St John’s Conventual Church. In 1716, the Maltese artist Alessio Erardi was commissioned by Grand Master Ramon Perellos y Roccaful to paint the vaulted ceilings with magnificent scenes, depicting the life cycle of the Blessed Virgin Mary.